A Brief History of Driver Education in the UK

This unique resource material summarises the early history of driver training, with explanations of how it became a cottage industry and how successive government regulations have been imposed on the way driving instructors are trained and supervised in the way they conduct their training. It also looks at how the industry, through the efforts of various associations, committees and individuals, has elected to make its ‘top-end’ echelons more professional. It continues by covering the development of educational advancement from the early days of the Diploma in Driving Instruction to the current stage of potential for Doctorates in Professional Studies for a few instructors to come.

It explains why it is now even more important for driver education generally, road safety specifically and professionalism in the industry incidentally, for continued professional development be progressed in the driver educational industry.

It ends with a look forward to some predictable changes in the next ten years.

Driver training is changing now, probably more rapidly than at any other

time in the past hundred years of motor vehicle ownership. From very strictured

beginnings, through a pre-war period of privately own schools of three,

four or more instructors; then to post-war periods of bureaucratic control

of self-employed freelance operators there is now a degree of professionalism

that, if the challenge is taken up, can lead to a fully professional industry

of respected driver trainers and testers.

This appendix was originally written as the introduction to my Doctoral project; then as the length of this particular “Setting the Scene” chapter grew and grew, it became apparent that it needed to be a stand-alone item as an Appendix. In this form it provides a reference point for those reading and studying the project, and yet can also be available to those who wish to fill in lacunae in their own knowledge of the driver training industry. There has also been considerable interest shown in publishing it in part or whole; although at the stage it wa first written (2001) I was also calculating the time and efforts needed to extend this appendix into a more detailed and personal history of the driver education industry.

A PERSONAL HISTORY OF DRIVER EDUCATION

IN GREAT BRITAIN

(A hundred years

of trial, error and success 1903-2003)

SETTING THE SCENE

It is implicit that an essential by-product of this Doctoral project is

the need to set down in print for the first time the basic facts with

the addition of a few opinions about the background to driver education

in Britain over the past hundred years.

As a starting point this might be best place to disabuse one particular myth referring to the motoring Emancipation Act of November 1896. Many people, especially broadcasters and quasi-motoring writers, often wrongly refer to this as the day that the “Red Flag” was removed from the roads. Prior to 1896, successive governments restricted the speed at which motor vehicles could drive, mainly to prevent excessive noise and inconvenience to other road users; and it is true that in the earlier days of motoring a man with a red flag was required to walk in front of any mechanically propelled vehicle. But this specific requirement to carry a red flag was dropped ten years before the 1896 “Locomotives on the Highway Act”, which raised the speed limit to a wonderful 14 mph.

Essentially this 1896 Emancipation Act removed the need for the man to walk in front of the vehicle, effectively keeping speeds at no more than four miles per hour. Therefore it was this Emancipation Act that allowed vehicles to move at whatever speed they could – fourteen miles an hour was still a target rather than a limit for most vehicles. Britain was able to catch up with the United States and most of Western Europe and allow their road vehicles to drive at speeds even faster than the horse drawn vehicles they were destined to replace. .

Naturally this step forward did not bring with it any requirement for the training or testing of drivers. Education in the use of motor vehicles was still a long way away. In 1903 the rise in the number of motor vehicles on the road brought about the need for vehicle registration and driver licensing; ostensibly for the funding of new and repairing older roads: hence the title remembered by many as the “Road Fund Licence”. However there was still no test to be passed before getting a licence to drive. The 1903 Act introduced driving licences, which permitted holders the freedom of the roads, and also the 20 mph speed limit ‘in built-up’ areas. Unfortunately the law did not define precisely what constituted a built-up area, and local authorities appeared to be divided into pro-and anti- motorcar agencies. This speed limit lasted until 1930 when the term 'de-restricted' applied to speed limits outside towns where vehicles could travel as fast at they wished. That right existed for more than fifty years, when following a press report of a A.C. Ace sports car being tested in the early hours on the M 1 motorway at 190 mph, led to the almost immediate imposition of a maximum of 70 mph on dual carriageways and 60 mph on single carriageways.

Unfortunately there are many drivers who still call the “National Speed limit” sign a ‘de-restriction’ sign; and treat it as one as well.

Historically driving instruction has always been a cottage industry (albeit inside a motor vehicle moving at 20-30 mph). Driver training probably began as a real form of a commercial venture in Great Britain about 1909-10 when a number of driving schools and training organisations opened their doors. The first recorded school that I discovered was the Pilot School of Motoring of north London, now long since defunct. However, launched just after this, in south London in October 1910, was the British School of Motoring Ltd. The proprietor was a Peckham doctor’s son, Hugh Stanley Coryton Roberts of Clapham. Soon after setting up in business he moved to the centre of London where he opened his ground floor offices in Coventry Street on the corner with Leicester Square. Later on he was to rent out a floor of the premises to the newly formed motor vehicle organisation – which was called the Automobile Association – and it was not long before this body too had to move to larger premises, eventually finishing up at Basingstoke. BSM also moved fairly soon afterwards into premises at 102 Sidney Street, Chelsea, where they remained until 1982.

However in the early days, the intentions of all driving school owners were to encourage those who had bought motorcars to learn how to handle them and, of course, to convert their carriage drivers and footmen into chauffeurs.

As the 20th century developed motorcar ownership rapidly extended, and learning to drive became a solitary, occasional and extremely unofficial affair. Car dealers sold cars; and quite often their salesmen (there were very few saleswomen in those days) would take new purchasers out for an hour or two to explain the basic principles of handling their new toy. Most of the training as such was concerned with the complexities of starting the vehicle, and then learning how to steer followed by many miles of trial and error experimentation with gear lever and clutch. No wonder chauffeurs were called ‘warmer uppers’: someone had to do the dirty work.

Learning how to stop was quite easy, if any driver failed to do any of the above things properly the vehicle usually stopped of its own accord. However, on occasions, new owners just relied on the presence of other vehicles or road users, or any solid pieces of street furniture, to help them to stop.

On the other hand, learning road procedure was a totally different affair. If boats had a rule that steam must give way to sail; no such rule obtained on the roads. Steam – or its successor – the infernal combustion engine, (please allow this deliberate if Freudian slip)… gave way to nothing unless that something was bigger or more substantial than itself. Once under way nothing would convince a driver to pull up unless it was to his advantage. White lines, give way signs and “Halt at Major Road Ahead” traffic signs were still only glimmers in the eyes of our parliamentary and civil service masters.

Road procedure could be simply summed up as:

“Keep the wheels on the ground and look where you are going”.

Changing gear was more difficult; these new automobile were without the luxuries of synchromesh gears. Automatic gearchanging mechanisms had been introduced in the United States as early as 1904, but had not caught on with British manufacturers. Subsequently new drivers never considered themselves skilled until they had learned how to match their engine speed to that of the vehicle’s rear wheel speed by means of the sheer physical effort of coordinating separate foot operating skills whilst manipulating the gear lever and without losing too much control of the steering wheel. People were usually grateful to acquire a car, and then to play with it until they became sufficiently proficient; during which time they frightened horses, pedestrians and passengers alike. It was on 12th February 1898 that Henry Lindfield of Brighton, gained the distinction of being the first driver killed as a consequence of a road crash. Although he only sustained injuries to his leg, the shock sustained by the subsequent amputation of the limb was enough to kill him.

My father often told me the story of when he was a young boy, being taken by his father, to the village of Broadway in Worcestershire; Broadway was so called I assume because of the massive width of its single main street. Granddad knew there was a car owned by one of the local landowners and, surely enough, dad and granddad were lucky to see it huffing and puffing towards them. Heading for it, but coming from the other direction, was a sedate pony and trap with another member of the gentry at the reins. The street was at least one hundred feet wide and probably two hundred and fifty yards long. Both road users inexorably moved towards each other at a closing speed of about twenty five miles an hour; on the obvious collision course that was apparent even to a four-year old boy. Closer and closer they came, each driver convinced of their own inviolable right of way, and that the other road hog would move out of the way.

Of course neither of them would, each convinced of his own ‘right’ to continue. Not only did my father witness a typical road traffic accident of the early 1900s, he was able to describe so graphically for many years afterwards; and, of course, he also became privy to the “real cause” of most road traffic crashes. Driver and Road User Behaviour.

Even a four-year old boy could recognise the cause of most road traffic incidents as stubbornness combined with reluctance to do anything about it. My father called it learning by blundering instead of learning through wondering. I am sure this tempered my father’s attitude towards his fellow road travellers for all of his working driving life, and I know that my own approach has always borne this particular driving lesson in mind too.

Learning was never required to be accompanied by training. Trial and error ruled the day. And, although the number of vehicles, in comparison with today’s massive gridlocks, was very sparse, constant crashes still managed to kill and maim drivers, passengers and any innocent passers-by who were usually too amazed to get out of their way. Mr Toad, of Wind in the Willows fame and driver extra-ordinaire, was certainly based on genuine examples of new car owners and was in no way a figment of Kenneth Grahame’s imagination.

It never occurred to new drivers that there was any skill involved in road procedure. Their cars were big and noisy. Surely cyclists, pedestrians and others could easily hear them coming and should keep out of their way. In some ways, these views are still echoed by academics who view driver training given by professional instructors as limited to teaching vehicle controls, whereas only skilled educational psychologists are capable of teaching "behaviour". I have spent most of the past 45 years trying to explain that the best educational psychologists in the world are driving instructors whose 'patients' are not lying down on a coach, but steering through busy traffic at 30 mph.

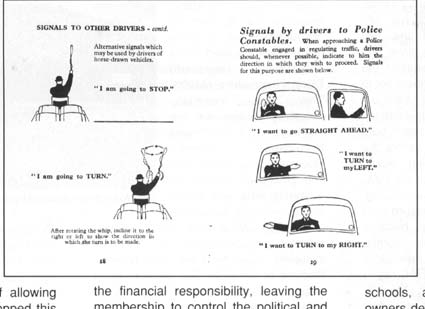

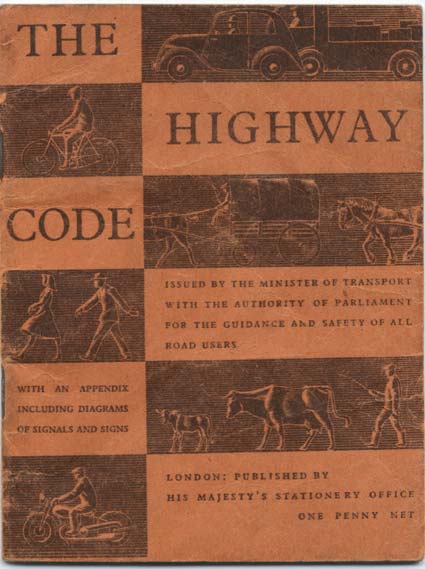

With less than a million vehicles on the road in 1927 road deaths peaked at 5,329; more than 4,000 road users were killed on the roads in Britain each and every year between 1930 -1934. A Highway Code, priced one penny, was published in 1930 to help combat the escalating number of road traffic accidents. Most other European countries had introduced driving tests, but the United Kingdom, Eire and Belgium alone in Europe still lagged behind. This disastrous situation was partly remedied in 1934 with the introduction of the Road Traffic Act of 1935, which culminated in the introduction of 30 mph speed limits, pedestrian crossings and car driving tests. The driving force at the Ministry for Transport was Oliver Stanley MP. However, by the time the new Act received royal assent, his replacement as Transport Minister, was Leslie (later Lord) Hore-Belisha, whose eponymous pedestrian crossing beacons looked after the interests of pedestrians for the first time.

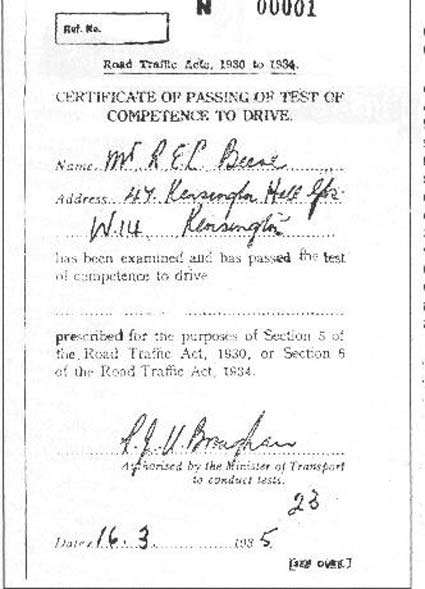

Early in 1934, following an open Civil Service competition, Captain R S D Stuart was appointed as the first Chief Driving Examiner. He and his merry band of eleven supervising examiners and 250 putative driving examiners offered free driving tests from 13th March 1935 until 1st June 1935. Provisional driving licences, costing five shillings (25 pence) and lasting for three months, were issued from the 1st April to enable would-be candidates to gain practice whilst accompanied by a full licence holder. In many cases the full licence holder would have bought their licence the week before when no test was required. I knew one of these people very well. Whilst I was waiting to take my own driving test, some fourteen years later, my mother quite often cheerfully accompanied me, although I know that she had never touched a pedal or steering wheel in her life.

Although there is no genuine record of the first person to pass the new legally required test in June 1935; the BSM has always proudly exhibited in their boardroom a certificate entitled number N 0001 (probablay one of 26; but this was the first pass from batch N) issued three days after these trial tests had begun on the 16th March 1935, by Mr R J U Brougham driving examiner number 23 of Captain Stuart’s 250 examiners, possibly to a BSM student, a certain Mr Beene, of Kensington. It is also worth remembering that those who took and failed these mock tests in those first three months between March and June did not lose their licence if they already held one.

The DRIVING TEST

It was not until the introduction of the driving test in 1935 that any serious attempt was made to co-ordinate the ways in which people learned to drive. However, for all their forward thinking skills, as demonstrated by the introduction of a ‘testing’ system for new drivers, no one in authority saw the need for any parallel form of structured driver training. Thus an examination was devised that had no teaching equivalent. And, of course, what made the situation even worse from both training and testing points of view, was there were no really proven ‘driving teachers’ from whom potential examiners could have been recruited. This style of bureaucratic thinking was to continue for another thirty-five years and more.

It was at about this time that the first trade association was formed. A group of driving school owners, led by Colonel Atherton, formed the Motor Schools Association. This was based at the offices of CMI Products at Finsbury Park, in north London. It was not generally realised at the time that Colonel Atherton was the proprietor of the company that made dual controls and that part of the aim of the association was to push for the fitting of driving school cars with dual controlled pedals.

Both the RAC (Royal Automobile Club) and the MSA (Motor Schools Association) formed their own independent registers of ‘qualified’ driving instructors and schools, at about the same time in June 1935. Each organisation laid down its own version of the basic teaching skills and examinations that were needed to register. Those instructors who wished to claim any independent form of registration or who sought a semi official recognition of their driver training skills were able to qualify with the RAC or MSA. In order to pass the RAC test you had to give an observed lesson to an RAC staff member; the decision to pass was in the hands of the regional officer manager. To pass the MSA test you had a written exam, followed by a short practical test with an MSA Board member and an inspection of the office and waiting room facilities This latter also included a toilet facility check: one for each gender. In effect there were two registers, one of instructors (RAC) and one of schools (MSA). It was not until many years later that the RAC admitted schools and in 1963 that the MSA allowed individual membership.

Successful candidates were entitled to display the relevant registered L-plates at their offices and on their teaching vehicles. Needless to say, there were no training courses attached to these examinations either. Most new instructors learned their trade by watching others and picking up hints, before trying their luck and lack of skills with real pupils. Others jumped in at the deep end; if they liked it, they carried on. That much has never changed. The only help ever offered from the Ministry of Transport was by listening to what their pupils told them after passing or failing the test. Indeed when I first began teaching people to drive for money, I was told that the best way to learn the trade was to follow genuine on-test candidates around a route and then practise on each one until I had learned all the routes.

Until 1973, successive Ministries of Transport and their examining staff gave no practical assistance of any kind to professional trainers. Indeed any examiners who were ‘caught’ talking to instructors before or after driving tests were quizzed quite severely and threatened with disciplinary action. The driving test had remained a mystery to pupils, the public and instructors alike for more than thirty-five years! Instructors used all means to borrow failure forms to see where they could improve their teaching skills. Others read the guidelines issued to new learners in a sequence of booklets called the DL68, precursors to the Driving Manual, except they had been issued free, mainly to failed test candidates. Many instructors never ever bothered to discover that the DL 68 was merely an extension of the DL 26 (the failure form) or that the hieroglyphics on the DL 25 (the examiners’ marking sheet) were in fact simply an examiners’ shorthand for the same headings. Even the system of ‘minor, serious and dangerous’ assessment marking remained a secret.

Examiners were required to sign the Official Secrets Act, and those who ever spoke about their job, or talked to instructors about ‘testing’ matters, could be sacked. They had to learn by rote, and use only a standard examiners’ script on the test. In 1974 when the MSA Director General and I were invited to visit the Examiners’ training establishment at Harmondsworth, where we gleaned some of the secrets of examiner training, we were similarly threatened. In one of my first driving books I published and explained the examiners’ official wording for the first time. Almost immediately I was called to task about this by the then chief driving examiner and charged with breaking the Official Secrets Act. I was content to remind him that if that were the case, then every examiner broke the Act forty times a week by using this ‘secret’ vocabulary in front of candidates. Nothing more was ever said.

Until 1956 most driving schools were operated as small private businesses with a school proprietor running five to ten motor vehicles from a high street, or back street, office. The only exceptions were those larger schools that operated on a national or regional basis. Exceptionally, of course, the British School of Motoring had flourished to become the largest private driving school company in the world. The reasons for the BSM financial success hinged dramatically on a number of successful law suits against the Crown at the end of the second world war which helped to pay for the freehold on virtually all their hundred and eighty assorted office premises in towns and cities all round the country. As a result of much of this additional largesse , BSM grew from being a nationwide driving school to a very large business conglomerate, BSM Holdings Ltd , which included an engineering College, a car hire company, an airfield or two, and many other diverse business interests. However the story of the British School of Motoring and how it progressed needs to be the subject of another book. Sufficient to say that it probably became the largest potential driving instructor training school and dual controlled car hire company in the world. In the past twenty years the changes of ownership of the BSM has been rapid and sometimes difficult to identify.

I have digressed somewhat and need to return to the beginnings of change and to look at how they affected instructors themselves; rather than to the bosses who owned the schools but were not involved in any teaching.

Like hundreds of other instructors in the late 1950s, I took both the RAC and MSA qualifying examinations and became a member, and then a committee member, of both organisations. However even though my peer group instructors were numbered in hundreds, there were thousands of other instructors teaching driving who held no qualifications at all beyond holding a full car licence themselves. Many others had never passed a driving test themselves, because they had gained their licences during the war or before tests became compulsory. I even know of a few who never possessed a driving licence at all. Whilst he was cleaning the windows at the school he was asked if he could drive, and was immediately offered a job as an instructor. He passed his own test about three months later, much to the surprise of the local examining staff.

This free-for-all came to an end with the onset of the Suez conflict in 1956, which introduced petrol rationing for the first time since World War 2; and brought with it, the suspension of driving tests (and driving lessons) because driving examiners were seconded to the role of petrol rationing officers . Most of the larger driving schools simply sacked their instructors, whilst virtually all of the smaller schools closed down and these instructors also became unemployed. What may not be realised by today’s instructors is that there was no such thing as home collection in those days. All pupils attended an office and waited in a waiting room for their instructor to return. Schools were run like launderettes, and probably many of today’s laundry businesses are on the sites of old driving schools. Home collection and cut-price lessons were critical factors in the following years and certainly brought to an end the era of the medium sized – ‘launderette’ style of driving schools.

When petrol rationing ended in 1957 it coincided with Harold Macmillan’s “Never had it so good” speech , which saw the reduction in deposits on the purchase of new and second-hand motorcars. Former and new instructors saw the opportunity to buy their own cars and set up in business on their own; instructors who had previously been employed saw the opportunity for a larger slice of the cake to meet the new and ever-increasing demand for driving lessons. At that time a driving test was fifteen shillings (75 pence) and driving lesson fees had all naturally been at least sixteen shillings (80 pence). The cottage industry became the norm. It also saw the price of driving lessons drop from an equivalent of something more than the driving test fee to a figure slightly below it.

Driving lesson fees have generally stayed below the test fee ever since, with the gap ever widening. The test fee in 2001 is £37.50 and driving lesson fees generally vary between £10 and £18. A driving lesson fee today, based on common sense and reflecting full costs, would probably be more than £45 an hour; which is exactly what I paid my local plumber last week, and he only used a large wrench compared with letting me drive his van – badly – for an hour or so. Incidentally, in 1957 BSM instructors were paid a weekly wage of £3.10 shillings (£3.50) for a basic 32-hour week, at a time when the national average income was about £10 per week. Overtime was essential to live and was regarded compulsory for those who expected to remain in post.

Initially when driving tests first began there were no legal controls over, or requirements for, the training, examinations or qualifications for, those who taught driving. It was only following strong representation by the Motor Schools Association, through its then president, Sir Harwood Harrison MP for Eye in Suffolk, in the years from 1957 to 1962, that the format of an initial voluntary register was passed by Parliament. Although Harwood had done all the work (with the assistance of members of the MSA’s Board) the actual early day motion, which kick-started the Bill into life, was approved on the 22nd February 1962 by the House of Commons, it was presented to the House by Will Old labour MP for Preston constituency. I was fortunate at that time to be sat in the Speaker’s Distinguished Visitors’ Gallery overlooking the chamber, much to the surprise of many of my colleagues who were herded in the people’s gallery. It was only many years later that I let slip that the Speaker had been my own local MP at the time, and his wife was my wife’s head teacher. All I had asked for was a seat and was treated as a distinguished one – if only for a few hours.

The voluntary register continued on this basis until January 1970 when a sufficient number of instructors had qualified voluntarily, to warrant government compulsion of the Register. The growth of driving lesson business at that time was due to the post-war baby boom (the ‘bulge’ as it was called) as they passed through childhood and entered their late teen ages and early twenties and were ready and willing for driving lessons and car ownership.

It was also around this time that the proliferation of local associations of driving instructors began. The MSA plan for the voluntary register had been that driving schools should be registered, but by the time that the register was founded it only covered individual instructors. Until 1982 the format of the ADI examination remained the same. The theory examination consisted of five essay type questions followed by thirty multiple response questions. Successful candidates were then invited to apply for a practical driving test. Only when this was passed could instructors apply to take the third part. The theory test had to be changed from its essay style format as Supervising Examiners were not able to devote the necessary time required for marking them.

Today there are only a few ‘employed’ driving instructors in the traditional sense of the word ‘employment’, in the industry. Virtually all car-driving instructors are self-employed, that is, they work from home and operate under a localised, or sometimes an optimistic, trading name. However, a few truck and bus driving instructors (who may wish to remain outside the ADI examination and registration system, unless they combine car training with their vocational vehicle training) are actually employed by their appropriate training companies. The Driving Standards Agency is currently running a voluntary register of truck vocational instructors and intends to make registration (by examination) compulsory within the next three or four years. Many instructors combine the business of truck and bus training, as similar training and testing skills are needed.

INSTRUCTOR TRAINING

Basic training in the industry begins at trainee instructor level; and training can also be needed and given to anyone who wants or has been told to lift their standards to grades 4 & 5 . Because the DSA lays such great store on the need for instructors to improve their gradings from a 4 to a 5, (less so from a 5 to a 6), most instructors see that by achieving a grade six accolade they will have something they can actively sell to their clients as proof of their teaching skills and abilities. Newspaper adverts often make reference to the fact that this particular instructor is a ‘Grade Six’. Regrettably many more advertise the fact they are cheaper than anyone else around. It is also interesting to note that whereas the DSA grade instructors from 6 (top) down to 1, when they refer to their own staff they allocate them from box 1 (well suited for promotion) down to box 3. Box 3 denotes examiners who are considered unsuitable.

The more recent years of driver education can probably be dealt with more simply. Anyone who has been an instructor for more than ten years will be well aware of the changes that have been made to the way their earn their living and the ways their professional lives are being controlled. However in those years between 1957 and 1991 changes also took place at dramatic rates.

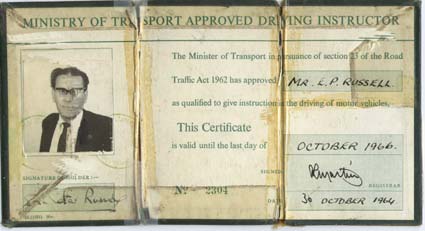

When, in October 1964, a total of 2008 successful instructors from the 3020 who took the voluntary tests in April and May that year, were told they had passed, they became the nucleus of the ADI Register and I am still vaguely proud of my ADI number 1,888. Curiously enough the two instructor and driving school representative bodies at the time, the RAC and MSA, were both against the ADI exams, as was the BSM, and advised their members not to join this new register. Instead they continued to negotiate, separately, for recognition of their own qualification, but not the other, instead.

The peculiar situation of the MSA appearing to support the ADI register through its inception to implementation and then being against it becoming compulsory is easily explained. When initial plans and details had been drawn up, the intention was to have a national register of driving schools, not instructors: and certainly not a register for instructors only. The writer, who had taken both RAC and MSA examinations before the ADI Register came into being, remains convinced that neither the MSA nor the RAC Register examinations were very taxing. Nevertheless organisation pressure held out, and when the Register became compulsory in the eighteen months following June 1970, those instructors who were in the MSA or RAC were excused from taking their Part One ADI examinations.

It was at an MSA Conference in Droitwich, in Worcestershire in February 1971, that a government offer to the industry on the future for trainee instructors was put and lost. The Ministry of Transport’ Registrar, Bob Martin, proposed that for any new trainee-driving instructor to be licensed, he or she would need the support, and signatures, of four existing ADIs. The MSA Board of Management, who were nearly all ‘driving school owners’, voted against this because they felt that it would interfere with their opportunities to expand. Other instructors who wanted to train their spouses for the register also voted with the driving school owners. The proposal was rejected to the great chagrin of many single-car operators and, in my view, to the detriment of the industry.

Many non-represented ADIs regretted this decision at that time; and in the past thirty years the whole industry, except for instructor-training companies, has probably regretted it too.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATIONS

Amongst the associations which also started in those busy years between 1957 - the beginning of modern driving instruction — and 1980, various ones shone for a time and then most of them went down with the sun. However there were two success stories in 1957. First of all the Motor Schools Association founded the Institute of Master Tutors of Driving (IMTD), as a freemasonry-styled club for driving school proprietors.

The Institute of Master Tutors of Driving (IMTD) was formed by and from the 1957 Board of Management of the Motor Schools Association (MSA) as an opportunity for respected driving school owners to have their own private club or institute to represent their views. Only school owners and senior managers were invited into membership. Part of the hidden thinking behind the institute was that it also served as a ‘training ground’ for future MSA Board chairmen. And when I was formally invited into membership of the Institute in 1968 it was noticeable that each IMTD chairman normally served for two years before moving on to become the MSA’s chairman for a further two years.

The then leading figure in the industry was the MSA’s Director General and later, President, of the IMTD, Pat Murphy, who entered into a dispute with the MSA’s retiring Chairman, Mr Frederick Spencer-Tucker, whose response to IMTD’s initiative, was to form an ‘instructor-based’ trade association called the ‘Association of Registered Driving Instructors’ (ARDI) based at Spencer-Tucker’s offices at Slough. In spite of the dispute, the two organisations ran alongside each other quite smoothly. Although ARDI was eventually dissolved it went through a series of metamorphoses before its members became the nucleus of Driving Instructors Limited. More of this later, but a few years later it eventually became the Driving Instructors Association.

However, throughout the late fifties and early sixties a number of other people tried desperately to extend the numbers of instructors professional associations. With the advent of the new Government Register in 1964, with Robert (Bob) Martin as its first Registrar, many local associations were formed by groups of local ADIs who found that by uniting they could advertise their expertise to the world at large. Ten local ADIs, including the local BSM manager founded the Southampton Driving Instructors Association, with myself as its voluntary unpaid secretary, in the first week of November 1964. We immediately held a meeting and agreed to advertise our joint success in the local press in the form of a block advert. Such was the success of our efforts that we found it necessary to become an association with a formal constitution. It is probably the longest established of the local ADI associations, although later when they amalgamated with their neighbours from Portsmouth and District, I believe that it now continues under the name of the Solent Association.

Other local associations, federations, group practices, clubs and other variations of joining together for a professional image, sprang up at the same time and many more since then of course. A few putative National Associations were launched. Some lingered awhile, many barely scratched the surface or left a footprint in the dust of history.

One group was actually called the “Proffesional D I Association” (with two f’s and one ‘s’). They didn’t last long either.

Many attempts were made to unify those associations that did stay the course. Some instructors did it by joining all of them, seeking office and then working from within. Others tried it by calling meetings of all known chairmen, secretaries and officers at numerous venues including private houses, pubs, British Legions, and College premises. The only one that had any success was the National Joint Council. This was a direct result of the efforts of the IMTD and it succeeded mainly because of the threat to petrol supplies in October of 1973 during the potential petrol-rationing scare caused by war in the Middle East again.

One or two national groups were also courted briefly (with high class lunches and even cigars) by the Transport and General Workers Union in an effort to ‘Unionise’ ADIs. The union bosses, who included the famous Frank Cousins, did not appreciate that very few ADIs were any longer ‘employed’ in their sense of the word; and certainly that those who were employed had employers who didn’t accept unions.

Today the IMTD still flourishes with less than 85 members who join on an ‘invitation’ only basis. At one time IMTD had nearly all the industry’s leaders in membership, including, for a brief time, Denise McCann and Norman Radford, chairman and training director respectively, of the BSM. Miss McCann was a very forceful lady and is still revered at the Institute of Advanced Motoring of which she was one of the original founders. Photographs of her with various other dignitaries and other mementos still line their boardroom walls. It was almost certainly as a result of her pressures that no other professional, working driving instructors have ever been allowed representation on the IAM’s governing council either.

Stanley Roberts had met Miss McCann during the mid-1930s in her capacity as an interior designer of note. Their rapport was such that she was invited to join the BSM board and on Roberts’ death just before the war she inherited his mantle as chairman and managing director. Stories about her and her methods of business are legendary, but I found her a sweet old girl really who, when I had to take her out to lunch on behalf of IMTD, put her hand lightly on my knee and surreptitiously slipped me a couple of twenty pound notes to pay the bill. I know that the IMTD’s treasurer of the day, Ron Miller, would have died to see so much spent on lunch on IMTD’s behalf, had I put in a claim.

One of Denise’s early edicts in 1957 was that every BSM manager should take the IAM test and then make sure they were elected onto the local regional committee.

Another simple but effective edict was that if anyone complained they were sacked.

The IMTD still recruits its membership from across the whole spectrum

of ADI organisations. But these days its influence is more usually exerted

in the ADINJC that it helped to found. Nevertheless the IMTD still apparently

provides a training ground for all the NJC’s officers almost exactly

in the same role it did for the MSA thirty years previously.

.

Gerald Nabarro, forthright MP and staunch motoring publicity pundit, was

instrumental in founding the first ADI association to be built on solid

business like lines. ‘It has to be a business or else it will fail

miserably’, was his opening remark. ‘You need to have a working

committee with a chairman who is paid for his efforts.’ was his

second; and his final remark – which most unsurprisingly worked

was “If you want me as chairman I shall require £5,000 per

year”. He then explained that this was just to cover his expenses.

Driving Instructors Limited was launched at the Union Jack Club in London

and became the first truly democratic national institution for instructors

to operate using efficient, business-orientated, but still democratic

principles.

DIL’s Board of Directors were nominated from the floor at its inaugural meeting, and hinged on leading figures from the instructing world, and included Graham Fryer, (now chief executive at DIA), Griff Mostyn-Jones (then NAADI), and Arthur Morris, of the BSM, who had risen from being a BSM manager to become deputy-managing director. The life of DIL was a very short but merry one. Shortly afterwards the BSM had changed hands. In 1971, with the onset of the ADI Register, and the need for compulsory qualifications for all instructors, Denise McCann had wisely sold her business to two bright, young entrepreneurs of the 1970’s. Anthony Jacobs (now Sir Anthony) and David Haddon, breezed into the driver training business almost like a pair of asset-strippers, but they did change the business structure of the company quite remarkably. Instructors were required to become self-employed, except for staff instructors and some managers. Initially when the new bosses took over, the first thing they changed was the training programme. They expected to double the number of training cars within a year or two. Their success was obvious and soon BSM became the major training force for many future ADIs; when they headhunted me in 1976 as their new head of training my role was explained perfectly.

“We know we are training our future competition, so we don’t want lots of well-trained instructors. We just want them to keep our cars safe and to stay with us until they have repaid their training fee loans”. This was my brief. My role was to retrain their staff instructors into what was required by the Department of Transport. In 1980 the Inland Revenue began to look more closely at their guidelines about self-employment and within a year or two BSM looked at ways in which they could launch the BSM as a franchised operation. BSM even found another trading company to buy out. They bought the Spud-u-Like hot potato franchise to get to know franchising better.

In 1980 David Acheson, a franchise specialist and former UK boss of the Kentucky Chicken Company, replaced David Haddon as BSM’s new managing director with instructions to make the franchising system work – and stay legal. He lasted about two years. Naturally there were almost continuous ongoing jokes about having a microwave oven inside each BSM pyramid on the roof of their cars to cook a chicken for pupils who passed and a spud for those who failed.

A slight digression about these pyramids is that Anthony Jacobs himself designed them, but they were fractionally higher than the boot space in the fleet of BSM’s Triumph Dolomite cars. Second-hand car dealers soon became expert at identifying dimpled boot lids on cars from Engineering Educational Trust Ltd who were the single, previously registered owners: ‘one very careful owner, but quite a few not so careful drivers’. The first time a car plus pyramid was driven through a car wash it did seventeen pounds worth of damage to the pyramid and seven hundred pounds damage to the car wash.

Initially David Acheson tried to franchise individual branches as a private venture for individuals who were invited to buy them as a speculative business venture. Naturally this failed partly because the operators had no idea of how driver training worked, and in also due to the fact that at least half the instructor strength of any branch had to be fully qualified. BSM had always operated a very adept “flying squad” of Approved instructors who would go out to branches where Supervising examiners might visit. But this essential lifeline was no longer available under the branch franchise system.

Later, BSM tried again, this time in 1983, where all of the instructors were given individual franchises. Although the system has come into various forms of criticism, the freelance-franchise approach apparently still works; but who benefits most may be open to discussion. Even the AA the Driving School copied the best of BSM’s franchise system when they opened their school ten years later.

Meanwhile the National Joint Council of ADI Associations had began to make progress. The Council was formally launched at a meeting in Fulham on 30th October 1973, with HPC (Pat) Murphy as chairman and myself as secretary of its initial steering committee. The founding member organisations were the MSA, IMTD, ICTD, (The Institute of Classroom Teachers of Driving, which closed down almost immediately afterwards), the RAC, BSM and NADI (The National Association of Driving Instructors) and SADI (the Society of Approved Driving Instructors). These latter two organisations almost immediately merged.

As soon as the success of the NJC was noted, three or four local associations pressurised the NJC for wider membership by including local groups as well as major players. This was eventually agreed and local associations could join on a basis of ‘one association — one vote’, regardless of the size of their membership. Although this was seen as democratic it also meant that a vote by the delegate from a local group of twenty or so instructors had the same value as one on the national bodies. Consequently problems on representation arose. Indeed some organisations, such as the Institute of Classroom Teachers of Driving continued their representation even though they had long since ceased to exist. Then the RAC lost interest in ADl matters at about that time and they closed down their RAC Register of ADIs, but their representatives stayed within the NJC. John Cowan, secretary of the RAC’s register, was the first to admit that the sole purpose of the RAC in setting up its 1935 register had been the recruitment, through the instructor force, of new members for its road patrol service.

Probably because of the influx of smaller groups, and of the way the NJC’s council re-elected themselves each year, the MSA also felt compelled to leave. So the BSM remained the only national organisation — (although they have never represented their franchised instructors by asking for their views) — which still stays to this day in the NJC. Incidentally the NJC later changed its title to that of the ADI NJC in order to gain alphabetical precedence in any listings of consultative bodies.

Driving Instructors Limited, in the format envisaged by Gerald Nabarro, did not last very long. But it did point the way to running a successful organisation. This factor was seized upon by one or two leading lights in the ADI world who had become disillusioned by the failed attempt to unite other factions. Two ‘national’ associations were from the north, The Society of Approved Driving Instructors (SADI) based in York, amalgamated with the National Association of Driving Instructors (NADI) in Manchester. Jointly they became known as NAADI, and then they also merged with the Motor Schools Association (MSA) in 1977. Pat Murphy, the then director general of the MSA, chaired the meeting, held at the Hotel Lily, Fulham on the 17th February 1977.

The combined Boards of MSA & NAADI passed a Motion proposed by John

Jackson (MSA) and seconded by Graham Fryer (then with NAADI) that both

organisations should merge their combined assets and membership. For a

few hours the industry, for the first and only time, officially had one

governing body. Sadly once again the merging association bosses reneged

on the democratic decision of their governing bodies. Although the Motion

had been carried it was never ratified. It soon transpired that potential

loss of office, and possibly loss of face, and other personal benefits

felt by some of the senior officers at the time were the real cause. NAADI

closed down a few years ago with the ill health of its sole remaining

director, Griff Mostyn-Jones.

The last, and quite notably the largest, of the national associations

to be formed was the DIA. The Driving Instructors Association was launched

on 1978. It had the initial financial support of an international insurance

brokerage that specialized in re-insurance of driving school vehicles

. From the very beginning it attracted many new members, especially trainee

and newly qualified instructors

DIA was formed as a direct result of two separate events:

• The failure of the MSA and NAADI to merge in the early 1970s;

and

• The partial success of the Driving Instructors Limited which was

felt to be successful, but the structure of which was ahead of its time.

What had been envisaged by DIL was a proprietory company which would take care of all the financial responsibility, leaving the membership to control the political, technical and instructional paths. Accordingly the DIA soon attracted enough members to make it a viable success. The reasons why so many new ADIs joined is that they saw an organisation which is not governed by their competitors, or driving school bosses who wanted to keep control of the industry for themselves. They saw that the future could lie in the hands of the individual instructor. The DIA membership outstripped that of the MSA within two years. Later, in 1989, it moved to its own premises on the outskirts of London, and later moved to its present home in the industrial heart of Croydon, yet within easy reach of the M25.

It is also interesting to note that for a number of years the Driving Instructors Association, had repeatedly applied to join the NJC in its capacity as a ‘national representative body, only to be refused. This was in spite of the fact that DIA’s own membership strength was about 10,000 ADIs; greater than all the other organisations combined; and in spite of the fact that on a one member association, one vote, there was never any danger of them ‘taking over’. The argument put forward for this refusal was that the DIA had asked for sight of the NJC constitution before paying its initial membership subscription.

The NJC’s governing council still continues to rule the council as it always has; but its representation is limited. Apart from BSM their membership now consists of twenty smaller associations most with an average membership of twenty or so. Democracy is not quite the order of the day there; one organisation has only one vote; and new members are not allowed to stand for office until they have been in membership for some time, and each successive chairman and officers are apparently confirmed in office by the outgoing council, who expect to be voted back in en-bloc.

Nevertheless the NJC training policy has paid off, and many instructor trainers have been through the training courses first begun in 1977. At one time the NJC briefly flirted with the idea of recruiting individual membership, but dropped this when it met with no real success. At the end of 2001 it has been suggested that they try to recruit individual instructors again, but no details of representation or fees is available.

Initially the NJC seemed to have inherited the MSA’s habit of social and national conferences although it could be that the IMTD’s influences on the MSA are now shown influencing the NJC in this instance. Before 1980 all national instructor conferences were usually convivial family affairs culminating with the re-election of the same old gangs. But these were changed and events took on a much grander scale; and they were working conferences and exhibitions instead of jolly days out combined with a few working sessions. .

National Conferences and Exhibitions on the scale of Drivex, held from 1983 to 1994 at Wembley, Silverstone and Donington, had never been known before; but they brought a whole new perspective on view. Previously national organisations had fought to have their own committees’ standards of quality imposed on members. The DIA opened its membership to anyone who wanted.

Trainee instructors were accepted because it was recognised that they needed more help in their first few months of qualifying than at any other time. The DIA also brought a fresh look at management by committee. At every annual general meeting the voting for the new General Purposes Committee takes place ‘from the floor’. All those who stand have an equal chance of being elected, with no question of waiting for ‘Buggin’s turn’ for office. Each newly elected GPC then elects its own chairman and secretary for the year and the committee are allowed to get on with their roles of representation of members’ views to the DIA executive, to the DSA and internationally, to and through, the IVV (The International Association for Driver Education). Perhaps the DIA’s greatest ‘unsung’ success has been its range of training publications. These range from the Driving Instructors Manual which is the only loose-leaf book of its kind. It covers the whole everything that a driving instructor should know coupled with the benefit of a regular up-date service so that copies do not go out of date with each change of law, pricing or regulation.

In the early 1980s the MSA also went through its own cathartic change. By 1970 it had prospered enough to purchase its own substantial premises in Fulham, SW6, valued in 1980 in excess of £120,000. The block of four separate offices, toilets and shower facilities, eight separate garages and a training school capable of seating thirty students, had been bought for £4,000 ten years earlier. However, through lax control of its business and insurance advisers, the MSA’s Management Board, between 1976 and 1979 had allowed two people, one on the MSA’s Board and other its recommended insurance broker, the freedom to set up a secondary business, called the ‘Motor Schools Agency’, by ‘passing off’ as the MSA. This partnership took a few financial gambles, including an expensive magazine which failed. As a result the MSA, found itself owing an initial sum of more than £40,000 which increased monthly as legal costs and interest fees mounted.

Unfortunately for me, in many ways, 1980 was the time I was invited to replace Pat Murphy as the MSA’s Director General. Pat’s excuse for early retirement had been his ill health; this was almost certainly exacerbated by the knowledge of the debt. I assumed he had been aware of the financial crisis that was looming and chose to hand over the problem for someone else to discover and solve.

It was twelve months before I first became aware of this potential debt, and of the role that the MSA might be called on to play. I was forced to take legal advice to prevent facing a long, involved and very expensive court case that we had been told we would win, but the litigants involved might plead bankruptcy to avoid paying their costs and any damages. I supported a proposed merger of the MSA with the DIA. The hope was that this would have allowed the combined association to settle the MSA’s debts and yet still keep their assets safe. This would also give a free rein for a joint Motor Schools and Driving Instructors Association to control the industry with a common board of management. The proposal even had Department of Transport support, and may well have allowed control of the ADI Register to be in the hands of instructors, in a similar way that the Law Society and the British Medical Association have control over their respective professional members. However, the MSA’s board was persuaded to stay separate from the DIA; and I moved to the DIA in the hope that the MSA might still change its mind in the interests of unity and saving the assets.

As a result of the potential for a substantial court case, the MSA were advised to settle out of court and sold their premises for £71,000. Most of this was eaten up in legal and settlement fees, and they moved to rented premises in Stockport under the two-man business partnership of Jim Beckett and John Lepine which lasted a few more years, before Jim dropped out, and John took over as sole general manager. In his capable hands the MSA has continued to flourish; and John has proved an excellent leader of the MSA.

However, in comparison, the DIA has grown both in size and capability even more dramatically. Driving Magazine, and Driving Instructor, were and still are unique publications, with international recognition. The DIA was able to use the power of its huge membership, and went outside the industry to obtain independent ratification and moderation of new examination standards and status. The Diploma in Driving Instruction has also been a remarkable example of the DIA’s national and international success. The DipDI was conceived in 1981-2, developed and then taken to the Associated Examining Board and they accepted the idea. Within eighteen months the first series of examinations was held; seven years later I was one of a team negotiating with Middlesex University to have the Diploma accepted as a foundation year’s points credit towards a degree – and higher degrees in Driver Education. On this level at least professionalism is already obtainable within the industry through accepted academic routes.

Nearly eighteen years after it was launched, with thousands of successful Diploma examination passes, the Assessment and Qualification Alliance – is very interested in changing the style of the Diploma examinations to suit more clearly the needs of the 21st Century. Details of some of these suggested recommendations are shown more fully in appendix three of this project.

Had the Register of Approved Driving Instructors been a register of driving

schools, as so many driving school owners demanded in 1962, perhaps the

history of driver training in Britain would be completely different. Certainly

there would have been far fewer than the 30,000 plus instructors around

at the turn of the 21st century. But whether the whole business would

be franchised, as the BSM tried to do in 1980, with non-ADIs operating

large branches in each town; and smaller ‘group practices’

of Instructors working together we shall never know. But the path to professionalism

in one form or another has re-vitalised and re-generated the industry

in a form that Stanley Roberts would never have understood in 1910

THE INDUSTRY TODAY

The estimated total membership of the two national trade organisations

in April 2001 runs currently at:

DIA 9,560; and the

MSA 3,760 .

(Recent figures for 2007 indicate that memberships of the only two large national associations are:

DIA 13,950

MSA 3,640)

However there is a considerable amount of cross membership too. There are probably about 11,500 ADIs who belong to one or both. Although DIA publish their membership total regularly up-dated according to bank receipts or direct debits, other organisations are often reluctant to state their actual paid up membership. This is natural of course as they hope to gain more influence with the DSA by quoting maximum numbers; but when annual financial returns are made at AGMs it is relatively easy to check the veracity of membership statements.

More recently two other national organisations have been formed. They are the ADI Federation, based in Northamptonshire with a membership slightly in excess of 500; and the Association of Driving Instructors Business Club, based in Bradford, which claims 2,800. The Federation has never been offered consultative status, whilst the Bradford group had their consultative status removed in 2001, possibly because their membership figures did not match their claims.

There are probably less than 15,000 instructors in the country, whose sole full time business is teaching driving. Some do it part-time in conjunction with another job (Fire service, Police etc); others are retired and give part-time tuition only as a means to supplement their pension. Very many would like to work full-time but cannot get enough business. So their part time status is very much an involuntary one.

Promotion, such as is found in academic, commercial or business life, does not exist in the driver training industry. And this is the crux of the whole problem presently facing the industry. Once an instructor is registered as an Approved Driving Instructor he or she may remain on the DSA Register until they choose to retire. Although there is a legal requirement to be re-tested every four years or less and to pay the re-registration fees, nothing else is required. However quite often the reason given for not renewing their licence is that quite a large proportion of instructors cannot afford the four-yearly renewal fee (£200). This has to be paid before the expiry of the existing certificate for instructors to remain on the Register. Those who fail to pay by the due date are removed immediately. This makes it illegal to teach for money or money’s worth from the date they forgot to pay their fee. Anyone caught doing so can be prosecuted and is then not allowed to rejoin the Register for a period determined by the Registrar, as ‘not a fit and proper person’.

Only a very few people can claim to have the entrepreneurial skills to establish a large school. They need to control (using franchised instructors who are not legally ‘employed’ of course) a dozen or so cars. In practice many of those who follow this path never qualify as instructors themselves. They use their management and business skills to greater effect instead. In many smaller cases they simply act as an advertising, recruiting and booking agency, whilst the instructors provide their own cars, but all working under the same localised school name. In other cases, such as the BSM or AA the Driving School, all the cars are supplied, and replaced regularly, however, the instructors, once they have taken up the franchise, are often usually responsible for finding their own clients, and bookings. Those customers who apply to local offices for lessons are normally allocated to newly franchised operators, in order to begin their ‘book’.

Nevertheless once instructors have qualified and have decided to stay in the industry, many options exist for them to gain additional status – and the potential for extra business – provided they are willing to look for and take these opportunities. In some cases this is purely for their own benefit as part of their desire to become better instructors, or to learn more about the trade, industry or vocation they have selected.

Every year more than two and half thousand new instructors qualify. A similar number leave. However, once they have qualified, many of these 2500 or so new instructors face the prospects of paying sums of up to £350 per week for being part of their particular training company’s erstwhile franchise system. The franchise fee can often cost more than the new instructor’s gross income. The franchise conditions are fixed – usually for a year – with very strict conditions imposed preventing instructors from leaving the franchisor or of continuing to work in the same locality as an independent instructor. Needless to say, those who have failed are still required to pay back their various loans borrowed to pay their training fees.

Most successful instructors eventually see their only path to business success is to set up on their own. There is very little profit in working a franchise, although there is not always a lot more gained by working independently, until it is possible to charge sensible fees. Indeed many franchise holders leave the industry at the earliest opportunity because their fees and other running costs are greater than their earnings.

Although there is a very low success rate of potential instructors making it through to full ADI status there is a tremendous business potential in training new instructors. Indeed many driving schools have completely abandoned the business of teaching learner drivers because it is so much easier to get money from those who want to teach driving. New learner drivers are unwilling to pay more than two or three hundred pounds for their training. But those who feel they would like to teach driving are easily parted from sums of two or three thousand pounds, because they assume they will soon get their money back. Sadly many do not even get past the first two stages. According to statistics supplied by the ADI Registrar, at least 30,000 would-be instructors begin some sort of training every year. Nearly all of them fail at the first two fences and never try again. However those whose business is in instructor training continue to flourish at the failed trainee’s expense.

The latest attempts by the DSA, following on from the failures experienced with the attempts to control training of instructors through the NJC in 1979 and the two separate Instructor Training registers ADITE (The approved Driving Instructors Training Establishments) and DIARTE (The DIA Register of Training Establishments), may finally be successful. At last, twenty-three years afterwards, there is the glimmer of real hope for progress. The two bodies have merged to become a single body, ORDIT, the Official Register of Driving Instructor Trainers, and it is anticipated that all trainers – as well as their premises – will soon be registered and monitored.

The ADITE register, supported by the MSA and the BSM, was content to register premises – provided at least a proportion of those involved in the actual training given by that establishment had been tested.

The DIARTE register, supported by the DIA, required the official instructor training register to test and name every individual ADI involved in training. All individuals on this separate trainers’ register had been examined, supervised as needed, and found suitable.

As the industry enters the 21st Century with computerised theory testing for both learner drivers and instructors alike there is a desperate need for unity in the industry like never before. The current climate for creating better forms of continuing professional development (CPD) for all instructors will require all ADIs who intend to remain in the industry to change the way they operate their businesses. This will also affect the way that new trainee instructors are recruited, trained and encouraged to become more professional.

Because of the current pressures for openness in all government matters

not only are learner drivers (and their instructors) given every detail

of the requirements of the driving test and a detailed verbal and written

de briefing of what they did wrong; they are also given (well sold by

the DSA) all the answers to their theory examinations before they begin

to study.

One thing is certain, since the DSA has started selling its training and

testing books they have made a lot of money from them; especially those

giving answers to examination questions. This is in direct contrast to

their first four years of operation when the DSA lost six million pounds

– as a monopoly.

This does beg one straight question however:

When I first became a professional driving instructor over forty years ago my own pass rate was always around the 85-90% rate. I never let anyone take the test unless I was convinced they would pass. For many years the national pass rate for all instructors, most of whom had never read any books, been on any courses or even dreamt of visiting Cardington, was 49%. How can it be that today’s instructors, knowing all they do, and with all possible help find their current average pass rate is now 42%?

The following fully detailed marking sheet given to pupils and ADIs must surely help in some way. It will be interesting to see if the pass rate improves as a result of it.

THE FUTURE OF THE PROFESSION

Continuing professional development is the stated aim of the Driving Standards Agency. Currently they are expecting CPD to supplement or even replace check tests as a means of grading instructors. However precisely what form this CPD will be required to take is a matter for conjecture.

CPD can mean whatever you want it to mean. And when associations talk with the DSA it is obvious that they have open minds on the whole subject. About the only fact the DSA will disclose at this stage is that they want the industry to determine what they can find out for themselves, and what the various national organisations can offer to their members in the way of continuing professional development. For more than thirty five years now, I and a small number of trainers with similar aims, have fought every way to have driver training available in schools and colleges. I was able to demonstrate how thisc ould be done successfully in Wincheser and other places. Even now there are a few florward-lookiing head teachers who see the potential for the satisfactorily development of good driving attitudes in young and new drivers which will really set them up as "Safe Drivers for Life",. What a pity the DSA has never seen this as a way to gain some success for their own maxim: Safe Driving for Life". Nevertheless, perhaps they will one day.

C.P.D. could mean that an ADI who attends an annual or even a biennial

conference, will satisfy the needs of the DSA. Or it could be that delegates

would need to acquire a certificate of satisfactory attendance to qualify.

At the other end of the scale are the various external training, testing

and qualifications that are available which will be required. Experience

of teaching driving in grammar and other schools might even be acceptable

by the DSA as suitable for C.P.D. Accreditation.

A recent research programme undertaken for the Driving Standards Agency

by the Ross-Silcock and B.I.T.E.R. group, highlights part of the deep

malaise that has affected the industry for more than forty years. There

are quite a few good instructors who are very well established and who

are able to cope with the challenges besetting the rest of the industry.

Without a great deal of formal business advertising they always maintain

a waiting list of pupils. They also tend to charge more for their lessons.

But many more instructors scarcely cover their business costs –

a factor they sometimes only realise when they have to replace their main

tool of their trade – their motorcar. They fail to cost out their

lesson prices, relying on charging a pound or so less than their nearest

competitors. Later they find they cannot afford to replace or repair their

cars, and face two options: to leave the industry or to struggle on with

an unreliable vehicle. A sequence of breakdowns on lessons or test will

create a bad effect on the school’s name and precipitates its downfall

anyway.

During the summer of 2000 Ross-Silcock leaked a few statistics suggesting that the ‘average instructor is middle-aged, finds it difficult to earn enough money to make a good living and holds little in the way of additional qualifications’. However those who are busy are more likely to hold additional qualifications – and those who hold higher qualifications are more likely to be busy. Those instructors most likely to be available to answer telephone questionnaires are those who are not busy. On the statistics issued, and bearing in mind that all the surveys were carried out during daytime interviews over the telephone, there is a general degree of scepticism shown by various trade organisations into the validity of the survey. Instructors who are busy are unlikely to be at home during working hours. The publication of the full report has been eagerly awaited.

My own experience (whilst I was general secretary of the Motor Schools Association of GB, [1980-84]; and as general secretary of the Driving Instructors Association [1984-1994];) consistently indicated that about one third of those instructors who were members had taken, were taking, or intended to take in the very near future, some form of additional training and gain higher qualifications. The figures shown in response to questionnaires sent out or published in magazines were always much higher; but the weaknesses of these kinds of statistics are that they only show responses from those willing to take part.

The training options ranged from courses arranged by the Associations as part of their national and regional Conference programmes, through Diploma in Driving Instruction, to a City & Guilds 730 series Teaching Certificate. Some courses and training programmes were practical, following the vocational route; others were more concerned with the academic route; although, naturally, there is a need for a combination of practical and theory enhancement.

Choices available

The opportunities for additional qualifications currently available to

instructors include the following:

• Cardington Special Driving Test - although there are no specific

benefits for this, the ‘kudos’ of having been tested at ‘Driving

Examiner’ level and knowing more detail and understanding about

the examining system has its own advantages;

• National Vocational Qualifications - although these have had a

very poor reception in the industry so far ;

• DSA - ADI Trainer Qualification - for those instructors who are

involved in training new instructors, these courses are currently being

revamped under a combined DSA and Instructor Organisations initiative

ORDIT; It is hoped to make them compulsory later this year.

• DSA - Fleet Driver Qualification – for those working in

the fleet market (assessing and advising experienced company drivers);

a voluntary register is on stream with a number of training courses being

trialled. The DSA is also setting up its own alternative examination based

around the Cardington test and two other parts;

• Diploma in Driving Instruction - it is not the possession of the

AQA Diploma which gives it the greatest benefit, it is the knowledge gained

in studying that proves the value of the scholarship involved;

• Teaching Certificates – such as those issued by C&G(LI)

or by local City and County Councils and include Certificates and Diplomas

in FE;

• Middlesex University Certificates, Diplomas and Degrees, and post-Graduate,

Courses – these programmes are still in their infancy having only

started in 1995. Nevertheless a number of Masters and Bachelors degrees

have been awarded. Again no immediate benefits can be mooted; however

the credibility factor both from peer groups and clients is enormous.

This list is naturally not exhaustive; but it demonstrates those areas in which I have any personal involvement. At the time of writing I have been made aware of the extension of a new government scheme for additional training of selected driving instructors who will carry on the role of trainers for the National Driver Improvement Scheme . (NDIS). This will be a path that many may wish to take.

At the moment the NDIS operators will recruit any suitable ADI who is willing; however the payments are not truly competitive and long delays often occur before they are made. However the current NDIS policy of selection by cheapest price may probably change, as the Scheme becomes a more popular path taken by Police forces in their efforts to curb those who drive without due care and attention. The DIA is currently trialling courses for suitable instructors – through the combined Fleet/Corporate and NDIS DIA series of Training Courses which were first validated by the DSA in April 2000.

The outline ‘Ladder of progress’ – or ‘Pyramid of success’ as I have chosen to accept it now to be – open to instructors is demonstrated as a ‘Pyramid of Success’. Many of the various stages of extended continuing professional development have been around for many years; others are growing in popularity and recognition. Some, like NVQs, have been hovering around for a number of years, but they have not yet become properly established as a viable proposition for self-employed instructors. There will certainly be further qualifications availble as the role of the driver trainer expands to fill the needs of the Health and Safety at Work Regulations, and to meet government demands for safer drivers at all levels.

As with any promotional pyramid there can only be relatively few, from the thirty-five thousand people eligible, who are able and willing to reach, or are capable of reaching, the higher echelons. Nevertheless anyone who wishes to do so can make their best endeavours to achieve whatever success for which they are aiming. All that is needed are inspiration and motivation.

The Cardington Special Driving Test

The special driving test at Cardington was first established in February 1976 as an attempt by the then Department of Transport, in conjunction with the national driving instructor organisations, to improve the standards of individual driving instructors. This was the first mutual attempt by the Driving test organisation and instructors to help bring about higher levels of instructor qualifications. The first tests were conducted in March 1977, one month before the Driving Examiner Training Establishment was formally opened in April that year. The pass standard was based on the practical driving test that examiners are required to pass after their initial two weeks’ driver training course.

These efforts were followed a few years later, in 1983, by the development of the much more demanding written theory examinations, leading to the joint AEB/DIA Diploma in Driving Instruction.

Nevertheless, nearly twenty-five years later, the Cardington Special Driving Test is still acknowledged as the stiffest ‘A’ level practical driving examination. And it has been readily accepted in the industry as the national standard against which all other advanced tests need to be measured.

Background to the Cardington Test

The Cardington Driving Test is unique. It may only be taken by Approved Driving Instructors and it has been determined as the highest standard of driving test available to professional instructors.

The format of the test was originally conceived at a meeting between representatives of examiners and instructors, held in November 1976, at the instigation of the then Chief Driving Examiner Bill Smith.

Mr Smith invited two representatives of the Driver Training Industry, H P C (Pat) Murphy, Chairman of the National Joint Council of ADI Organisations and Director General of the Motor Schools Association; and myself as General Secretary of the NJC and Secretary of the Institute of Master Tutors of Driving.

The result was the development of an ADIs’ Advanced Driving Test, using the Examiner Training Staff and the Department of Transport marking system. It is important to remember that until this time no instructor had had any official access to this; and I well remember Pat and myself, walking through the corridors of the newly-opened driving examiner training establishment and reading the various examples of standard write ups of errors made and details of why pupils fail. We also left each with our own personal copy of a form DL25 and the training course notes. These days ADIs are given copies of the new revised versions of the marking sheet often even before examiners receive them

During the following four months Pat & I met regularly with Kenneth Hester, Deputy Chief Driving Examiner responsible for both Examiner Training and the ADI Register; and John Alexander, Chief Instructor at the Department of Transport’s newly opened Driving Establishment and his deputy, Ken Walkden, to devise an acceptable format for an advanced driving test which the best and most experienced ADIs could reasonably expect to pass. This was initially set at the same level as that expected of driving examiners after two weeks training.